Connection is the Goal, Mitzvos are the Path

In the beginning of Mesillas Yesharim the Ramchal writes:

When you look further into the matter, you will see that only connection with God constitutes true perfection, as King David said (Psalms 73:28), “But as for me, the nearness of God is my good,” and (Psalms 27:4), “I asked one thing from God; that will I seek – to dwell in God’s house all the days of my life…” For this alone is the true good, and anything besides this which people deem good is nothing but emptiness and deceptive worthlessness. For a man to attain this good, it is certainly fitting that he first labor and persevere in his exertions to acquire it. That is, he should persevere so as to unite himself with the Blessed One by means of actions which result in this end. These actions are the mitzvos.

The goal is connecting deeply to G-d and the path to achieving it are the mitzvos. The sefer Mesillas Yesharim itself is focused on doing mitzvos progressively better to achieve their intended goal.

Let’s take the first 2 lines of Shema as an example. The halacha states that we have to pay close attention (have kavanna) to what we are saying for the first 2 lines. If we don’t do that, we won’t get the full benefit from saying the Shema and it will not help us get closer to Hashem to the degree that it could.

It takes a reasonable amount of effort, just to observe the mitzvos, so we often feel accomplished just from the fact that we are observant. If we take a little step, and do mitzvos with intention and with a focus on connecting to Hashem, we will get much more out of them and will can avoid the frustrating plateauing state.

Let My RV Go!

Let My RV Go! – by Nicole Nathan.

Review by Batya Medad

Web site for the book

I never got up the guts to publically laugh at myself the way Nicole Nathan, the author of Let My RV does in her wonderfully entertaining book.

Let My RV Go! can be purchased in both eformat and as a “real book.†It was sent to me for review. I had no idea what to expect. It opened up a whole new world for me. I thought that I was the only one who felt “different†even though outsiders don’t see it. I study Bible and even give classes and lead tours of Tel Shiloh in Israel. But the real me will always be a bit different. In recent years I’ve requested that those giving our local women’s Shabbat shiur never ever use the phrase:

כמו ×©×›×•×œ× ×• ×œ×ž×“× ×• בגן….

Kimo sheculanu lamadnu bagan…

Like we all learned in pre-school…

I and others who are either converts or BT’s never learned in such pre-schools and it makes me feel very left out and rejected to hear such a phrase.

Let My RV Go! is about the bonding of two BT families and their adventures and misadventures on the way to spending a rather unconventional Passover. Adding to their Passover challenge and time limitations, they had been given an important package to deliver before the Holiday to a “mystery person.†Neither full name nor address, just a vague description of who he is and where he lives.

You need not know much about Judaism and Pesach to enjoy reading the book. I have no doubt that anyone who has attempted a family vacation in an RV, whether Jewish or not, will identify with some of the problems the families encounter. This is more than just a Jewish book.

By adding humor to all situations, whether between husband and wife, parents and children or navigating new roads, this is a book people will enjoy reading. Yes, I do recommend the book!

The message is that “it all works out in the end.†Yes, it’s an upbeat book with a happy ending, just the sort of book I needed to read.

Sharing the Joy: Your Shul and Your Wedding; Judaism and Positive Psychology; Iranian TV and Me

Shabbos … the Great Unifying Principle

Vayakhel 5774-An installment in the series of adaptations

From the Waters of the Shiloah: Plumbing the Depths of the Izhbitzer School

For series introduction CLICK

By Rabbi Dovid Schwartz-Mara D’Asra Cong Sfard of Midwood

Moshe gathered the entire assemblage of the Bnei Yisrael , and said unto them: ‘These are the words which HaShem has commanded, that you should do them. Six days creative activities shall be done, but the seventh day t shall be holy day for you, sabbath; a day of complete respite for HaShem. Whoever actively creates in it shall be put to death.

-Shemos 35:1,2

And let every wise-hearted person among you come, and make all that HaShem has commanded. The Mishkan-tabernacle, its tent, and its covering, its hooks, its vertical boards, its bars, its pillars, and its sockets. The Ark etc.

-Shemos 35:10-12

All that is called by My Name, and whom I have created for My glory, I have formed him and even made him.’

– Yeshyaya 43:7

Rav Yehudah said in the name of Rav: Betzalel [principal artisan of the Mishkan] knew how to bond and combine the letters through which heaven and earth were created.

-Brachos 55A

How did Moshe gather everyone together, and forge them into a unit? Why is the commandment of building the Mishkan preceded by the commandment of Shabbos?

The Maharal of Prague explains that anavah-humility, is rooted in pashtus-generic simplicity and the lack of any specialty. There is a certain infinite quality to simplicities non-delineation. Simplicity specializes in nothing in particular and so; can be everything at once. Committed to nothing, simplicity enjoys infinite possibilities. This is how the Maharal explains the hanhagah Elyonah-Divine administration of the cosmos, expressed in the theological concept of “Wherever one discerns the Holy blessed One’s Might and Greatness there one will find His Humility.†(Megillah 31A) The Humility/ Simplicity IS the Greatness/ Infinity. Considered more deeply, this is the basis of monotheism. It is the Divine “property†(for lack of a better word, for this word implies specialization, chiseled-definition and constraining lines as well) of anavah that “makes†HaShem k’vyachol-as it were, both the undivided “One†and the encompassing “All.â€

The roots of human ga’avah-ego and egotism, lie in the self-perception of individuality and specialization. That which we specialize in is what makes us salient and exceptional. “I am what YOU are not. I am capable of what you are incapable of, or, if your are capable of the same, I can do it better than you can.â€Â We are proud of what sets us apart and so; what separates and divides us is our pride. As any manager will tell you, a major part of teamwork is the surrender of ego. There is nothing more ego-deflating than to feel that one is a fungible, interchangeable part in a larger entity, a mere cog in the machine. But for collective entities to coalesce and integrate the balloons of ego must first be deflated.

The Izhbitzer explains that when a craftsman works to produce something it is intrinsically a distinctive, one of a kind item. Produced by his own individual mix of perceptions, tastes and faculties; it is as unique to him as his fingerprints and the antithesis of a mass-produced article.  As our sages expounded “just as their faces are dissimilar so too are their attitudes and perceptions (deos) divergent.â€(Midrash Tanchumah-Pinchos) This is true even in as rarified and superhuman a “craft†as prophecy. As Chazal taught “No two nevi’im-prophets prophesize in the same style.â€(Sanhedrin 89)

Logically, custom-made items should not be able to dovetail or interlock. Yet;  although the Mishkan was fabricated by individual craftspeople, each proud of their own unique talents and style, the individual components that they crafted were stitched, hooked, inserted in sockets, ringed or staved together to form a seamless whole. Oblivious to it at the time they plied their supposedly unique, inimitable specialties; they all conformed to the precise specs of a master plan. The Mishkan reduced one-of-a-kind artists to molds and die casts in a mass production assembly-line. When the Mishkan was complete and all could see how harmoniously everything fit together this observation raised their consciousness of the siyatta diShmaya-the Divine assistance that worked It’s Will through them.

They experienced a collective epiphany that it was HaShem, not they, who had actually built the Mishkan. They came to realize that they were no more than the proverbial garzan b’yad hachotzeiv– the ax in the hands of the lumberjack. The ax is an integrated implement uniting blade, handle and the pegs that bind them. Even if the ax was composed of sentient beings the blade could still not lord it over the handle or the pegs for none could accomplish their task or fulfill their role without the others. Moreover, even when their tree-felling missions are accomplished , the humbling realization that “axes don’t fell trees … lumberjacks do†would unite them in their true, cooperative, integrated identity as the lumberjacks implement, rather than as free-lancers working on their own.

The Izhbitzer asserts that Shabbos is the key to this awareness. The Shabbos concept lies at the core of every mitzvah performed l’shemShamayim –purely for HaShem’s sake with no ulterior motives whatsoever. He goes so far as to say that they are synonymous, that intent l’shemShamayim IS Shabbos by another name. I’ll attempt to offer a possible explanation for the Izhbitzer’s enigmatic axiom.

The Midrash teaches that the Divine Will for creation is described as nisaveh lo dirah b’tachtonim –He yearned for an abode amidst the lower spheres. (Tanchumah Naso 16) This seems odd. HaShem is transcendent, Existing outside of time in non-chronological terms; so how can any given time play host to HaShem? HaShem is omnipresent, Existing outside of place in non-spacial terms; so much so that Chazal tell us that HaShem is nicknamed HaMakom-The Place, because “He is the Place of the cosmos, the cosmos is not His place†(Bereishis Rabbah 68) so how can any given location serve as His abode? Yet … we also know that kedushas haz’man and kedushas hamakom – sanctified time and space are real, not delusions. HaShem’s dwelling place within the lower sphere of time is Shabbos. He ceased creating on the seventh day for His Will, that all of creation declare His Glory, had been done.

When, in perhaps the ultimate act of halicha b’drachav- imitatio dei, shomrei Shabbos cease their creative activity, they bear witness to the veracity of the Torah’s Genesis narrative. More than that, they bear witness that the creative activity of Genesis could cease because the goal of creation had been achieved. HaShem had his abode in the lower spheres in a cosmos in which every infinitesimal component part, and the grand macrocosmic whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, declare His glory. And so, every mitzvah performed l’shemShamayim, for HaShem’s Will and Glory alone, is yet another iteration of Shabbos; the accommodating time in the hospitable place in the lower spheres that provide HaShem k’vyachol, with a glorifying abode.

How did Moshe congregate everyone? How did he instill unifying humility in the hearts and minds of the formerly prideful, specializing craftspeople who, collectively, built the Mishkan for the Shechinah-HaShems Divine Indwelling? By first commanding them to observe Shabbos and by making the Shabbos concept clear to them.

Just as HaShem did not bless and sanctify the seventh day until all the work was done, until the cosmos was complete and perfect so too He would not allow His Shechinah into the Mishkan until it was complete and perfect. Had one peg anchoring the curtains of the Mishkan’s courtyard been missing or not engineered according to specs, the Divine Indwelling would have remained in the upper spheres. How then could the fabricator of the aron habris-the Ark of the Covenant have felt superior to the peg maker? One and all the artisans and craftspeople had been an implement, the ax wielded by the Divine Lumberjack.

~adapted from Mei HaShiloach Vayakhel Dâ€H Vayakhel

Nesivos Olam-Nesiv Anavah 1

Vayakhel – Revealing the Deep Greatness in All of Us

Parshas Vayakhel

This week’s parsha deals with the construction of the Mishkan (tabernacle). The Mishkan / Bais Hamikdash was the source of light for the world. The construction of its windows was unusual. In the Bais Hamikdash, the window openings were built to be narrow on the inside and wide on the outside. This allowed the light from within the Temple to illuminate the world without (as opposed to allowing the maxim of light from the outside to shine in). (Kings I 6:4)

Betzalel had the monumental task of constructing the Mishkan. The name Batzalel means, “In the shadow of Hashem.†The definition of a shadow is the absence of light. What is the significance of the light of the Mishkan and the darkness inherent in Batzalel’s name?

The Baal Shem Tov explained the verse in Tehillim, “G-d is your shadow†(121:5) Hashem, like a shadow, responds to your every move. The mystics offer perhaps a deeper interpretation. This verse suggests that the innate divinity in man, the tzelem Elokim – the Divine image in whose likeness we are created, is reached through embracing one’s inner shadow. What is the meaning of this?

The Megilah is the only book of Tanach in which Hashem’s name is not written. The Megilah’s authors, Mordechai and Esther wanted to maintain the true nature of the recorded Purim story in the same light that it originally transpired in and hence, teach a powerful lesson. Similar to life, the entire story can be perceived as an apparent random display of cause and effect. Only the trained eye sees Hashem in every nuance of the scroll.

In fact, Hashem’s name is encoded throughout the Megilah. The name of Hashem, can be found as an acronym in the words of various verses. In addition when the word melech / king is used without a direct reference to Achashveirosh, there is a secret hint to Hashem, the King of all kings. There is even a tradition that King Achashveirosh is a reference to Hashem, as this name is a combination of two words, acher (after) and rosh (first). Hashem is the first and last.

Like the hidden nature of the Megilah, costumes conceal the true identity behind a mask. Thus, costumes have an important role in the Purim celebrations. The pristine greatness of Mordechai, the tzaddik was hidden in coarse clothing. “Mordechai tore his clothes and put on sackcloth.†(Megilah 4:1)

Hashem Himself is said to wear clothing. “He wears light like a garment.†Like clothing, nature disguises Hashem. When one observes a sleeve move on a person, he does not perceive the arm itself, only the concealment around the arm. However, the intuitive eye sees the sleeve move and understands that it’s the arm within, that is performing the act. Similarly, the initiate can see nature / the world and know Hashem.

Hence, clothing does not only conceal, it reveals. Often the higher on the body a garment is worn, the less it conceals and the more it reveals. A crown for example, in essence does conceal a part of the body however, it is worn in order to reveal to the masses that this is the king. (This is the deep tradition for Jews to wear a hat. Unlike other garments of clothing, the hat is purely a sign of dignity). “Mordechai left the king’s presence clad in royal apparel of turquoise and white with a large gold crown…†(Megilah 8:15)

The challenge of life is to reveal the G-dly greatness deep in all of us.

The gemarah asks, “Resh Lakish said, ‘Great is teshuva (repentance), when sins done with intent are converted to accidental sins.’ However, didn’t Resh Lakish say (differently), ‘Great is teshuva for sins done with intent are converted to good deeds?’ The resolution (of the two statements) is; The first statement is true when the teshuva is accomplished out of fear of heavenly punishment; the second is true when the teshuva is preformed out of love for G-d.” (Yoma 86b)

Previously it was explained that all negativity in the world stems from one of three negative shells (klipah). These shells are so tightly tied to negativity they can never be elevated. For example, pig, an idol or the act of the sin itself. A person’s body mass is a consequence of everything that one has consumed. Throughout the duration of one’s life, food’s nutrients are ingested and become a part of one’s very being. If a person were to consume pig, he would become one with it in essence and he can never achieve a rectification. Only when one accomplishes a deep teshuva through “ahava rabba†/ great love, the impossible transpires and this negativity is elevated. (Tanya chapter 7)

Chasidus explains, Yom Kippurim is only like (a kuf means like) Purim. Therefore, the true day of atonement is Purim and Yom Kippur is only like it. Perhaps on Yom Kippur we repent out of fear, however on Purim it is through love, transforming even the negativity of the sin / darkness into light.

Light is far more potent when it radiates in the darkness as opposed to it shinning in already illuminated surroundings. This is the unique quality of Beztalel. Through the darkness of this most physical and crude world, he disseminated a great light to all of creation. The mystics interpret the name Beztalel to mean, in the shadow is G-d.

This is the true depth of Purim. It is when Mordechai is wearing the royal garments, a concealment in order for a revelation, the Megilah relates “.The Jews had light …†(Megilah 8;16). This is the light out of the darkness. This familiar verse is repeated as we apparently descend from the light of Shabbos into the darkness of the week, as the havdalah candle illuminates our surroundings. This candle is not the light of Shabbos. It is the light out of the darkness of the week.

The Megilas Esther (the scroll of Esther) means to be megaleh / reveal the hester / concealment. There is a deep tradition that the names of the 3 utter negative shells are, Amalek, Agag and Haman. Perhaps the secret of the mitzvah in becoming so intoxicated until one can’t discern between baruch / blessed Mordechai and arur / cursed Haman is precisely the aforementioned concept. “When wine enters, secrets are revealedâ€. Once a year, through the lowly act of inebriation we reveal our inner G-dly greatness. Just as the Purim story turned utter despair into our greatest celebration. The gallows were built for Mordechai, however, Haman was hung on it. So too in life, as on Purim, the greatest darkness / evil can be the very source of the greatest light.

Good Shabbos,

R’ Moshe Zionce

Originally Published 2/29/2008

Baruch Dayan Emes: Reb Meir Schuster ZTâ€L

Rabbi Dovid Schwartz in Hamodia:

Yesterday, on 17 Adar I, a neshamah that exerted its last ounce of strength while here in this transitory world bringing tens of thousands of neshamos to their soul-roots was, itself, returned to the t’zror hachaim with the petirah of Rabbi Meir Schuster, ztâ€l, after a long illness.

Reb Meir was the proverbial “legend in his own time,†as he carved a mythical niche for his name in the annals of the kiruv movement as an incredibly effective recruiter for a wide array of kiruv programs, baal teshuvah yeshivos and womens’ seminaries. And while he sought out new soldiers for the milchemes Hashem in a variety

of eclectic venues including Yerushlayim’s Central Bus Station; he was most identified with the Kosel Hamaaravi where he literally “picked them off the Wall.â€

Rabbi Yair Hoffman at Cross Currents

It is a sad day for the Torah world because of the loss of this great, great man. Rav Meir Schuster zatzal passed away today after a debilitating illness. This man was singlehandedly responsible for bringing more people closer to Avinu sh’bashamayim than entire outreach organizations. Without exaggeration, many tens of thousands of people came to Torah observance because of the actions of this man.

The greatest insight into this man was perhaps a shailah that was presented to Rav Elyashiv zatzal, when Reb Meir had lost his father. According to the Torah, the period of mourning lasts for three days. Chazal extended this period to seven days. Rabbinic extensions of halachos are universally observed in Judaism. Chazal tell us (based on Koheles 10:8) regarding Rabbinic enactments – “Kol HaPoretz Geder yeshacheno nachash – anyone who breaks the fence (on a Rabbinic law) deserves that a snake should bite him.†Yet, here things were different. Every day that Rabbi Meir Schuster was not at the Kosel, the wailing wall, was a day that Jewish people would not get a chance to be brought to Torah-true Judaism. Should he sit three days or seven days?

It was, of course, not even a question. Rav Elyashiv paskened that he may only sit for three days. Rav Elyashiv had never ruled in this manner for anyone else. Rav Meir Schuster was irreplaceable.

Meir Schuster hugged my brother

I met Meir Schuster in 1970, at the Kotel in my first days after arrival from Madison. I felt an immediate affinity for Meir. I had been in Madison. And he was from Milwaukee. I was looking for myself as a Jew.

And Meir was there, at the Kotel, a selfless one man endeavor who only wanted to make sure that every Jew who sought a Jewish soul from within would have someone to talk to.

In those days before the internet, when few people had telephones, Meir developed a network of people who would welcome wandering Jews into their homes, especially on Shabbat.

For years, Meir Schuster would arrive at the Kotel each day, to be there for fellow Jews who had no real home in Israel.

Bracha Goetz at rebmeirschuster.org

Reading the stories about Rabbi Meir Schuster that are just now being collected, I am transported back over thirty years ago.

It is 1976. The man who was to become my husband was praying at the Kotel. Larry had finished his time in a kibbutz ulpan, and was still volunteering in a development town in the Negev, when he decided to spend the weekend in Jerusalem. He was scheduled to return to the States a few weeks later, with no clear plans. Larry put a note in a crevice in the Wall and then prayed sincerely to find his path in life. When he finished, there was a tap on his shoulder. It was Rabbi Schuster, asking him, “Do you have the time?†Thank G-d, Larry did have the time, and he followed Reb Meir to a yeshiva for baalei teshuva where he began the process of finding his life’s path. After nine years of learning and teaching at Yeshiva Aish HaTorah, young wandering Larry became Rabbi Aryeh Goetz.

It is 1978, and after completing my first year of medical school, I was volunteering on the oncology ward at Hadassah Hospital, visiting with patients who were dying, while my secret mission was to learn the purpose of living. During my first few days in Israel, I went to the Kotel, and Reb Meir Schuster found me there. His purity and his sincerity came right into my heart. I began to study at the women’s division of Ohr Someyach, and the process of understanding the purpose of living began for me as well.

Lincoln and the Jews

From Abraham Lincoln and the Jews:

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, whose 203rd birthday we are observing, was a protector and friend for the Jews “In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity.”

At the outset of the Civil War the Jewish Community faced official discrimination as the legislation expanding the US Army restricted the chaplaincy to clergy of the Christian faith. Members of the Jewish Community energetically protested this exclusion. Petitions for change in the law, including one in the U.S. Senate presented by Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, later the author of the 13th Amendment ending slavery, were submitted. In response, President Lincoln wrote to Dr. Arnold Fischell on December 14, 1861:

I find that there are several particulars in which the present law in regard to Chaplains is supposed to be deficient, all of which I now design presently to the appropriate Committee of Congress. I shall try to have a new law broad enough to cover what is deferred by you in behalf of the Israelites.

Truly yours,

A. Lincoln

President Lincoln was good to his word and on March 26, 1862 the act was amended to allow for brigade chaplains “one or more of which shall be of the Catholic, Protestant or Jewish religion.” The community reaction and Mr. Lincoln’s responsiveness set an important precedent for the far more dangerous threat that was to follow.

From Lincoln and the Jews:

In January 1863, Lincoln revoked the only incident of official anti-Jewish discrimination when he countermanded Ulysses S. Grant’s infamous Order No. 11, which expelled Jews from Northern Mississippi, Tennessee and Kentucky. Lincoln also appointed seven Jewish generals to the Union forces.

What were the reasons for Lincoln’s concern and kindly attitude toward the Jews? First and foremost was the fact that by the time of the Civil War, Jews had become a factor in American life. During the Revolutionary War and the founding of America, Jews numbered a miniscule 2,500 out of a population of approximately 4 million. By 1840, they had only grown to 15,000, but 20 years later, in 1860, the Jewish population had risen to 150,000, out of a nation of 30 million. The Jews emerged from a relatively docile and unseen element in the population to a viable minority, striving for its own rights and recognition.

With the increased Jewish population, the future president knew Jews as admirable neighbors even in the little towns where he grew up.

Louis Salzenstein was a storekeeper and livestock trader in the town of Athens, Ill., near New Salem, where Lincoln spent six years. When Lincoln was postmaster, he collected the mail from “Old Salty’s” store, which served as the regional post office. He became good friends with Salzenstein, who was remembered by a town historian as “doing more than any other man toward bettering the improvements and the mode of living in this section.”

First Published 2/21/2011

Are Blogging Rabbis Good for Shuls; GTD Concepts in One Page; Adar, Simcha and Household Help mp3s

Stressed Out

Right now (although by the time you read this it would have been Sunday afternoon), I should be mired in preparation for a multi- defendant enterprise corruption trial which is scheduled to begin tomorrow morning. Yet the more I try to delve into transcripts of the hundreds of recorded telephone conversations and thousand of documents, the more I am distracted over some perplexing phenomena. Perhaps I am just procrastinating or maybe I’m in denial that the trial will actually start, but it troubles me that the more stressed out I become while attending to my daily mundane pursuits, the more spiritually disconnected I become.

Isn’t this counterintuitive? Shouldn’t it be the exact opposite? Aren’t we at our spiritual zenith during challenging or difficult periods in life? Isn’t that when, more than any other time, we achieve focus and clarity by crying out with fervor and sincerity to connect with Hashem? Why then, when it comes to the daily hustle and bustle, it seems that we’re just “too busy†to daven or learn

? Funny, but we don’t seem to have that problem with kashrus. When was the last time you said to yourself, “Gee, I’m too swamped to eat kosher. I better eat some treif.†I know what you’re thinking. Hey Kirschner, that’s not the same thing. Eating treif would require you to do something when you’re already too busy doing something else. It’s an entirely different matter to omit davening or learning because you’re too busy to stop doing what you’re doing. Somehow though, being armed with this knowledge doesn’t seem to prevent us from repeatedly falling into this abyss. At first glance, the obvious answer is that such is the very cunning work of the yeitzer hora. Fair enough, but simply recognizing that, by itself, doesn’t necessarily mean we will escape its grip. Frankly, if it were that easy, we would have little difficulty overcoming many of our challenges just by understanding that it is the work of the yeitzer hora.

Unlike many things in life, where a lack of clarity precludes us from sifting through the fog of the yeitzer hora, it really shouldn’t be that tough here. If anything, the busier and heavier our daily secular pursuits become, the need to spiritually connect with the Borei Olam becomes clearer. This is true if for no other reason than from a selfish desire to throw up our hands and beg Him to relieve us from our burdens. We seem to have little, if any, difficulty doing it for Shabbos. Why then is it so difficult to take the time out to daven, find a minyan or learn even for a few minutes each day to fulfill the mitzvah of kvias itim – setting aside a fixed time for daily Torah study?

Sure, the yeitzer hora relentlessly attempts to convince us that it is a mitzvah to miss a mincha or a maariv because we need the parnussa to pay yeshiva tuition. He tells us, “Don’t worry, while performing one mitzvah, you’re exempt from performing another mitzvah. It’s okay if you miss your shiur or cancel your chavrusa (learning partner) because you’re very tired, you worked very hard and you need your rest to be fresh for work tomorrow. You have to pay the bills, don’t you? You have to work hard for that promotion which will bring your more money with which to perform more mitzvos.â€

It’s all quite perplexing. We can actually feel ourselves becoming disconnected the more we buy into that gibberish. Even if we overcome it and go to minyan or daf yomi, we do so by ruminating over that which still needs to be accomplished. And that’s if we’re awake!

Some years ago, I observed a well-respected rabbi in shul take out his pocket date book and make a few notes (that was before the PDA) after completing his shemonah esrei. After davening, I commented to him that it surprised me to see even rabbis have things pop into their head during davening. He responded, “Of course, that’s the best time for the yeitzer hora to disrupt us.†Then he shared with me a very effective tactic. Speak to Hashem and tell Him your thoughts during the day when you’re in the middle of your mundane pursuits. It doesn’t take much time, you can connect with Hashem in mere moments and best of all, by the time the yeitzer hora figures it out, you’ll be done. That, in turn, will provide the impetus to make minyan, attend shuir and learn with your chavrusa.

Now, if only I can figure out a way to “connect†with the judge tomorrow and beg him to adjourn that trial.

Originally Published on Dec 6, 2006

First you Think in Secular and Translate for Yourself; Eventually you Begin to Think in Frum

I spent the first 25 years of my life big into non-conformity. I prided myself on digging hipper music than my high school friends, choosing a trendy college too cool for grades, eating vegetarian, camping through the USSR before glastnost, living in the East Village, and on and on.

Becoming a B.T. was the ultimate in non-conformity. One friend (now a prominent psychiatrist) tried to de-program me. Maybe I was a Ms Magazine subscriber but I couldn’t shake off that pull toward Yiddishkeit.

In other words, to so radically turn your back on your comfort zone–family, friends, career, even language–you have to be a risk taker, a non-conformist.

But…living frum. That’s the ultimate in conformity. Boy, was it hard the first years. Doing things just because it’s the frum way was, at time, impossible to digest. Squelching my well-honed instinct to disagree. Giving up T.V. All the forbiddens of Shabbos. Keeping a neutral expression at racist speech. Shaving my legs. Realizing that the right thing to do or say was pretty much the opposite of my instincts.

I think you have to be an actor to be a successfully assimilated B.T. And daven that after a while, you fully embody your character.

Originally Published Dec 13, 2005

Personalized Psak; The Case for Rabbinic Blogging; Are You Getting Enough Things Done

Personalized Psak and Guidance – The Rabbi Relationship Requirement

The Case for Rabbinic Blogging

Are You Getting Enough Things Done? (Concepts of GTD, one of the most popular organization and time management frameworks.)

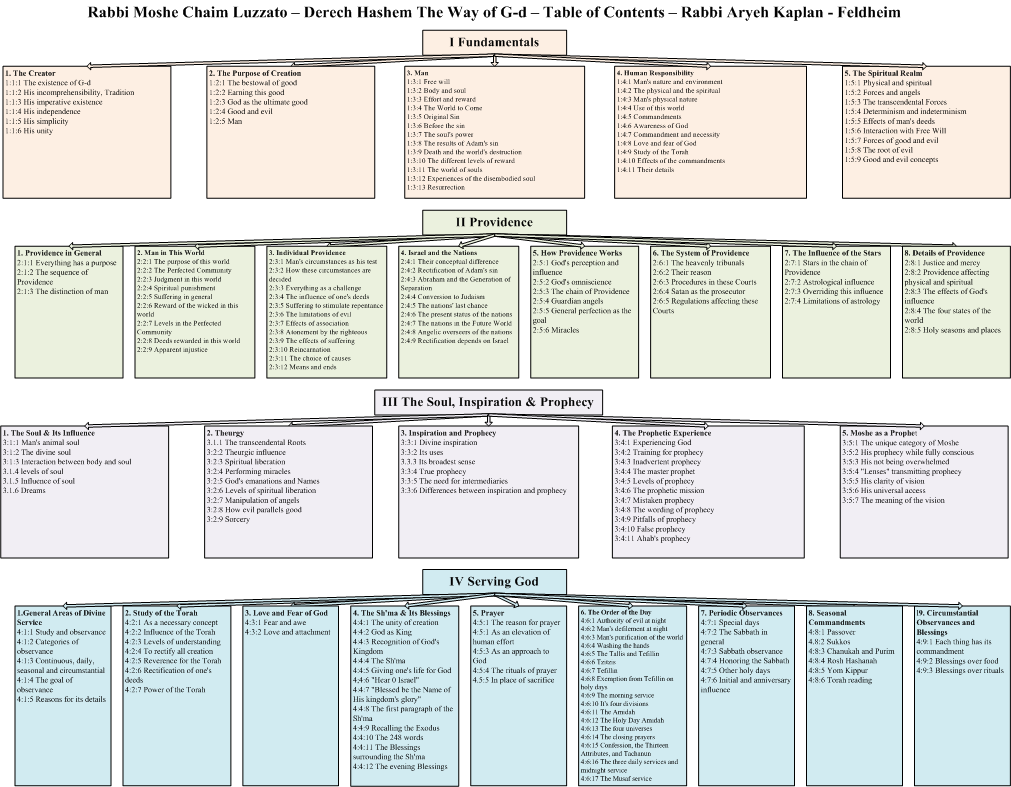

Derech Hashem One Page Overview

The Ramchal’s Derech Hashem is a must read classic for any Jew.

I’ve created a one page table of contents of Derech Hashem, which you can download here.

There are two translations available from Feldheim:

Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s translation can be purchased from Feldheim or Amazon.

Rabbi Abba Zvi Naiman’s translation and elucidation can be purchased from Feldheim or Amazon.

They’re both excellent and highly recommended to purchase and read over and over again to understand the fundamentals of Judaism.

Clarity at the Kotel; InfoGraphic, Video & Audio on Change; The Danger of Too Much Information

Thinking Inside THE Box(es)

Terumah 5774-An installment in the series of adaptations

From the Waters of the Shiloah: Plumbing the Depths of the Izhbitzer School

For series introduction CLICK

By Rabbi Dovid Schwartz-Mara D’Asra Cong Sfard of Midwood

HaShem spoke to Moshe saying: Speak to the children of Israel and have them lift an offering up to Me. Take My offering from anyone whose heart stirs them to give.

-Shemos 25:1

Make an Ark of Shittim-Acacia wood 2 ½ cubits long, 1 ½ cubits wide and 1 ½ cubits high. Envelop it with a layer of pure gold; it should be covered on the inside and the outside, and make a gold lip all around its top.Â

-Shemos 25:10,11

Betzalel (the chief artisan constructing the Tabernacle) built three Arks; two of gold and one of Acacia wood. All had four walls and a floor but no roof (i.e. the “Arks†were boxes, open on top). He inserted the wooden one within the exterior golden one and the interior golden one within the wooden one. He then coated the upper lip with gold. As such (the Acacia wood Ark) was covered on the inside and the outside.Â

-Rashi ibid

None of the furnishings of the tabernacle were made exclusively of gold other than the Menorah. (but I’m puzzled) Once a golden Ark was made, why was a wooden one necessary?Â

-Ibn Ezra ibid

Several peculiarities distinguished the Aron HaBris–the Ark of the Covenant from the other structures and furnishings of the Mishkan-tabernacle. The specs for its dimensions were in half, rather than in full, ahmos-cubits. Unlike the Menorah it was not made of solid gold but unlike the other wooden Mishkan structures and furnishings coated with metal, it was composed of three substantial inlaid boxes, akin to Russian nesting dolls, rather than plated with a paint-thin coating of gold or copper.

The Aron HaBris was the vessel for the Luchos HaBris–the tablets of the covenant and so it serves as a powerful allegory for human bearers of the Torah, talmidei chachamim-Torah sages and, in a larger sense, Klal Yisrael-the Jewish People. Chazal drew a metaphorical lesson from the design and structure of the Aron HaBris: Rava said (the fact that the inner and outer boxes of the Ark were composed of the identical substance [gold] teaches us that) “any talmid chacham-Torah sage, whose interior is inconsistent with his exterior (i.e. who is insincere or hypocritical, who lacks yiras Shamayim-the awe of Heaven) is no talmid chacham at all.â€(Yoma 72B)

Based on this homiletic precedent the Izhbitzer School provides many insightful interpretations about the design and structure of the Aron:

The Izhbitzer taught that in order to acquire Torah a person must view himself as incomplete without the Torah that, as was the case with the measurements of the Aron, that they’re only “halfway†to completion and fulfillment. On the other hand, if one only has an intellectual curiosity about Torah similar to an academic interest in other disciplines HaShem will not allow him to become a receptacle for the Torah. If a person feels as though he can live without Torah, he may study and contemplate it for years, but he will never truly absorb it.

The Izhbitzer’s younger son, the Biskovitzer Rebbe, explains that the reason for the three individual inlaid boxes was to demonstrate the Torahs intrinsically hidden nature. It is not merely that the true meaning of the Torah’s narratives, mitzvos and teachings often eludes us; the proverbial “riddle wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma,†but that there are three barriers that must be transcended and pierced in order to perform the mitzvos fully. The following impediments prevent people from committing themselves single-mindedly to the service of HaShem and, thereby, transforming themselves into abodes for His Divine Indwelling:

1. So many millennia have come and gone and so many “end times†have been predicted without the long-awaited dawning of the messianic era-kalu kol hakitzin. The dispiriting sense of hopelessness in Mashiach ever actually arriving cools our ardor for the mitzvos.

2.  The leadenness of our natures steers us towards undemanding, path-of-least-resistance, mitzvas anashim melumadah-rote performance of the mitzvos. Bringing a sense of awe, wonder and freshness to the performance of mitzvos time after time is very challenging when we’ve been trained to do the mitzvos from our earliest youth.

3.  The burden of our past sins weighs us down. We feel humiliated before HaShem and utterly convinced that our relationship with Him has been irrevocably broken.

The Biskovitzer explains that the midrash (Shemos Rabbah 33:3) interprets the pasuk “I am asleep but my heart is awake†as an allusion to these three barriers. “I†may be insensate to the end of days, but “my heart†— the Holy Blessed One, is awake, maintaining and stoking the very last embers of longing for the messianic era within me. “I†am deadened to the vitality of the mitzvos by my robotic, by-rote performance but “my heart†— the merit and legacy of my forefathers, who were trailblazers and who were forever breaking new ground, is awake. “I†am anesthetized and alienated by the ether of guilt wafting malodorously from the incident of the golden calf, but “my heart†— HaShem, my Merciful Father, refusing to give up on even the most wayward of sons, is awake.  The Holy Blessed One called for me to build the Mishkan. If the alienation caused by sin was truly irrevocable would HaShem ever have invited me to participate in the building of an abode for His Divine Indwelling?

He cryptically concludes that, of the three boxes, it is davka the wooden one that symbolizes the impediment of sin-engendered guilt feelings and especially, on a national level, the guilt engendered by the incident of the golden calf. Puzzling, because the Midrash Tanchumah that he cites (Parshas Vayakhel 8) says the Aron was made of Shittim wood to atone for the sin committed at Shittim. This is an apparent reference to the sin of licentiousness with the Moabites that occurred at Shittim and not referring to the sin of idolatry of the golden calf (that occurred at the foot of Sinai).

[A more direct reference might have been the Midrash Tanchumah from our own parshah (Terumah:10) that states; HaShem told Moshe “they committed a folly (shtus) and angered Me with the calf; let the Acacia wood-atzei Shittim come and gain atonement for their folly.â€Â The problem with the latter citation is that the Acacia wood in question is that of the mizbayach-altar and not of the aron.]

Rav Tzadok, the Lubliner Kohen, asserts that the essential aron was the one that was made of wood. Unlike inert-mineral gold, wood came from a living, thriving, flourishing tree. The Torah itself is referred to as “the tree of life.â€Â The atzei Shittim box in the center represents the ardent, almost libidinous, yearnings for Torah-chamidu d’Oraysa that are the necessary prerequisite for the acquisition of the Torah’s wisdom (cp Rambam Isurei Biah 22:21). While the sincere awe of heaven, represented by the interior and exterior golden boxes, contains, defines and sublimates the unbridled, wild infatuation represented by the wood.

Elsewhere the Lubliner Kohen notes that during the creation of Heaven and earth, the darkness preceded the light. He postulates that every personal or national advancement towards greater spirituality and “the light†must be preceded by, and grow out of, a darkness. It was not simply that the Shittim wood of the Aron atoned for the sin of the calf it was that the dark sin of the calf was an indispensable precondition that engendered the light of the Aron and, as the epicenter of its sanctity, the entire Mishkan!

The sin of the calf was motivated by Klal Yisrael’s desire for a palpable sensory-perceivable Elohim that would lead them. While directed towards the calf this desire was something dark and sinister. But the radiance and illumination of the Mishkan — a place where HaShem’s Indwelling was palpable, and the only site where all “seekers of HaShem†went to find what they sought (Shemos 33:7), followed and grew out of the darkness of the calf. Through the atzei Shittim, the shadowy “shtus†of the calf became part and parcel of the Aron’s and Mishkan’s radiance.

~adapted from: Mei HashiloachII Terumah Dâ€H Kol Middos

Neos Deshe Terumah Dâ€H v’Ahsu (the first)

Pri Tzadik Terumah inyan 8 page 152

Resisei Laylah inyan 24 pp30–31

REVISED 5:30 PM EST 1.30.14

A New Jewish Classification Scale

The Jewish classification system of Reform, Conservative, Modern and Yeshivish/Charedi has shown some wear and tear in recent years, as it’s often hard for people to see where they belong, and everybody is forced into a single square. I’ve come up with a new classification system that can be thought of as more of a scale rather then discreet categories.

At the beginning of the scale is the group that finds Torah Not-Relevant. They don’t believe or study Torah or participate in any Jewish observances.

The next point are those that find Torah Relevant. They may not believe Torah was received through prophecy at Mt Sinai, but they do believe it is an important document with many relevant teachings and rituals.

The next point are Jews that think Torah is Important. They generally believe Torah was received through prophecy at Mt Sinai and keep the mitzvos> Living a Torah lifestyle is an important part of their lives.

Finally are Jews who find Torah to be the Primary force in their lives. They may be learning in Kollel or working full time, but Torah learning and observance is the primary thing that drives them.

So the scale looks like this:

Not-Relevant———>Relevant———>Important———>Primary

A person may find themselves between two points of the scale as they move from say, Relevant to Important. In addition this classification is based more on internal factors, rather than external. Let me know if you think this is helpful.

Air Travel Davening; Canadian PM Strong Israel Supporter; Shul Members Give More

Dilemmas of Air Travel Davening

Coming from Ben Gurion on Monday, we were stopped for a short while for the Canadian PM.

It’s great to see PM Stephen Harper is such a strong supporter of Israel.

Let’s Get Away (From it All) … With Murder!

Mishpatim 5774-An installment in the series of adaptations

From the Waters of the Shiloah: Plumbing the Depths of the Izhbitzer School

For series introduction CLICK

By Rabbi Dovid Schwartz-Mara D’Asra Cong Sfard of Midwood

If he (the killer) did not hunt and trap to murder, but Elokim brought about involuntary-manslaughter through him, then I will lay down a space where the killer can flee.

-Shemos 21:13

[HaShem said to Kayin] “You are more cursed than the ground … When you cultivate the soil it will no longer yield its strength to you. You will be restless and isolated in the world.â€Â

-Bereishis 4:11.12

Kayin responded “Is my sin then too great to forgive?â€

-Ibid 4:13

Kayin left HaShems presence. He dwelled in the land of Nod (isolation) to the east of Eden.

-Ibid 4:116

We live in an era in which our lives are kinetic and restless. In every phase of life and during all of our waking hours, we are always on the go. Yet few people really seem to mind. The pan-societal consensus seems to be that whenever a person is on the move, that he is doing so for his own good.

Some people transfer to new universities or yeshivas in middle of their education. Others relocate to advance their careers. Even the increasingly rare “company man†who stays with one firm throughout his entire career will make frequent business junkets. The travel industry does not refer to the area between first-class and coach as business-class for nothing.

Most ubiquitous of all is traveling for pleasure. Stay-cations are indicative of a general economic downturn or of one’s own lack of financial success.  The old saying goes that “if you’ve got money … you can travel†and most people who have money — do. The rule of thumb for achieving greater social status through travel is that the further-flung the destination, the better the vacation.

People advance all kinds of rationalizations to validate their wanderlust. “Travel is broadening†they will say or they might claim “a change of scenery will do me a world of good.â€Â Still others associate their homes and offices with stress and tension and, impatient for the afterlife, their vacations as the precursors of the ultimate reward in the world-to-come; “I’ve worked really hard and I deserve some R&R.†Some will even couch their constant flitting about in religious terms.Â ×ž×©× ×” ×ž×§×•× ×ž×©× ×” מזל – “a change of location will result in a change of fortune.†(cp Rosh HaShanah 16B and Talmud Yerushalmi Shabbos 6:9).

But some latter-day nomads dispense with the rationalizations altogether. They travel lishmah, so to speak. They may not be able to articulate it as eloquently, but they are in general agreement with Robert Louis Stevenson who said “I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move.†Perhaps it is modern man’s relentless movement that robs him of the luxury of pausing to ponder; why this is so? Why is the great affair to move? What is the real subconscious compulsion, the psycho-spiritual dynamic at work, which induces us to travel for travel’s sake?

Rav Tzadok-the Kohen of Lublin provides an eye-opening and astonishing answer to these questions:

Like Kayin, we are wanderers because we are murderers. This is not to say that we are guilty of the most flagrant and literal forms of homicide. Stabbing, strangling, shooting or poisoning the victim is not required. Our prophets and sages taught that there are other sins that, while not causing the permanent irreversible termination of life, are still iterations of murder.

We’re all familiar with the Chazal that equates inflicting public humiliation to the point of blanching, with murder. (Bava Metzia 58B) Chazal coined a term “the three forked tongue†to describe sins of lashon hara–gossipy speech, because these sins kill three people; the speaker, the listener and the subject of the conversation.  (Arachin 15B) The prophet Yeshaya condemned another form of non-homicidal murder when he thundered “You that inflame yourselves among the Terebinth trees, under every leafy tree; that slay the children in the riverbeds, under the clefts of the rocks!†(Yeshaya 57:3 see Niddah 13A)

While those who transgress sins that do not rise to the legal and halachic definition of homicide are not sentenced to utterly abandon their homes and exile themselves to a refuge city or to the camp of the Levi’im they become unsettled, itinerant wanderers all the same. The Lubliner Kohen goes on to say that, the good news is, when we do begin to lay down roots in a particular place and achieve some tranquility and stability we can rest assured that we have been metaken-ameliorated these homicide-like offenses.

There’s even an intermediate condition during which, while we may be more or less fixed and established in a particular location, we are not really happy about it.  The normal state of affairs is that of חן ×ž×§×•× ×¢×œ יושביו-“every place is charming to its own populace.†(Sotah 47A) If, on the other hand, we do not find anything attractive or satisfying about our homes, neighborhoods, towns or workplaces this is symptomatic of having repaired and been forgiven for the deed that was in some way equivalent to murder but that the antisocial thoughts that motivated us to act as we did, still require tikun-repair and teshuvah-atonement. While our feet may not be itchy enough to take the first step in a journey of 1000 miles, our minds and spirits remain agitated, distracted and 1,000 miles away.

In his classic work of Hashkafah, Michtav M’Eliyahu (Strive for Truth), Rabbi Eliyahu Lazer Dessler, zâ€l, views the entire contemporary human condition through the prism of the Lubliner Kohens teaching. Writing presciently in the mid twentieth century he points out that never before has mankind been so murderous and, not coincidentally, so nomadic and adrift.

Weapons of mass destruction can lay waste to entire cities in a matter of moments.  Gossip is no longer something whispered in dark corners but a multibillion dollar publishing industry. Slander, inaccuracies and half truths coupled with a breakdown in civil discourse had transformed character-assassination by means of public humiliation into an international sport. Unparalleled pornography, lasciviousness and loose morals had disseminated the form of murder that the Prophet Yeshaya decried to previously stern and puritanical corners of the earth.

Concurrently, advances in aviation and other technologies made modern man substantially more mobile than his ancestors. From one end of the earth to the other, millions of people traverse unprecedented distances at previously unimaginable speeds. And while these travelers may dream that all this running about is advantageous to them or that they’re doing so for pleasure and entertainment (entertainment being synonymous with a deep-seated disquiet, distraction and scattering of the soul-pizur hanefesh) they are, in fact, just living through the curse of Kayin, humanities first murderer. Despite all of the giant leaps forward in technology man has never felt so rootless, anxious and insecure.

Imagine how much sharper Rav Dessler’s critique of modern man and how vindicated his linkage of high-speed, easily accessible travel with WMDs, the venality and universality of gossip and humiliation would be, were he writing today.

Virtue is always its own reward. So we already had ample incentives to avoid doing the many sins that our tradition teaches are equivalent to murder.  But if we needed an ulterior motive the Lubliner Kohen, has provided us with one. As the Torah is eternal HaShem “lays down a space where the killer can flee†and be free of the curse of Kayin in every generation.  Refraining from lashon hara, publicly humiliating others, withholding wages et al seem a small price to pay to achieve a sense of a rootedness, connectedness and tranquility via entry to the sanctuary surrounded by invisible walls of Torah and teshuvah — the space that HaShem has laid down.

~adapted from Tzidkas HaTzadik 82

and Michtav M’Eliyahu IV:Kavanas haMitzvos; Page 171Â

The Mixed Shul Kiddush; Change Thru Desire & Big Goals; Yisro; Selling Spirituality Pitfalls

Growth and Change are Hard – So What are We Waiting For?

R’ Micha Berger has written a fine essay pointing out that mitzvah observance is a means, and we need to do more if we want to achieve the goal of Torah and mitzvos. I’m assuming he doesn’t disagree with the Ramchal in the chapter on Human Responsibility in Derech Hashem where he says:

We therefore see that the true purpose of the commandments is to turn us toward G-d, bring ourselves near to Him, and thus be enlightened by His Presence, to avoid sin and other phenomena that lead us away from G-d. This is the true purpose of all the commandments.

In a post titled Getting Better Mileage from our Mitzvah Observance, I pointed out that according to the Ramchal in Mesillas Yesharim:

Observing mitzvos are indeed the means, but the goal is to continually growing in our connection to Hashem. If we don’t notice progress in that goal of closer connection, then we’re not getting the appropriate value from our mitzvah observance.

The Mesillas Yesharim also tells us what we’re doing wrong, we’re not focused on improving our performance of the mitzvos. We need to be more careful in their observance, and more mindful when we perform them. If we follow the Torah’s prescription in mitzvah performance, we will achieve the goal of continuous growth in our connection to Hashem.

In the previous mentioned post and a post around Chanukah time, I suggested we work on our Kavanna in the following four things:

1) Say one Birchos HaMitzvot each day with Kavanna

2) Say one Shema each with Kavanna

3) Start one Shomoneh Esrai each day with Kavanna

4) Say one Birchos Hanehenin each day with Kavanna

When Rebbetzin Heller was in the U.S. in November, I had the pleasure of having dinner with her and I mentioned the above project and asked her opinion. She said that if a person could do these four things daily, it would be transformational. She also pointed out that because we do these things every day, it is difficult to say them with Kavanna.

When a friend from Baltimore stayed by us for Chanukah, I mentioned this project. He also agreed that it would be amazing, but that it’s hard.

So that’s situation we find ourselves. If we can do some of the mitzvos that we’re already doing, with a little more Kavanna, we can take ourselves to a higher spiritual level and perhaps in the process we can motivate those around us to reach for higher levels. It’s hard, because of the regularity with which we perform these mitvos, but it’s definitely within our grasp. I’m still working on it and encouraging others who are interested to join me.

Yes, growth and change are hard – so what are we waiting for?